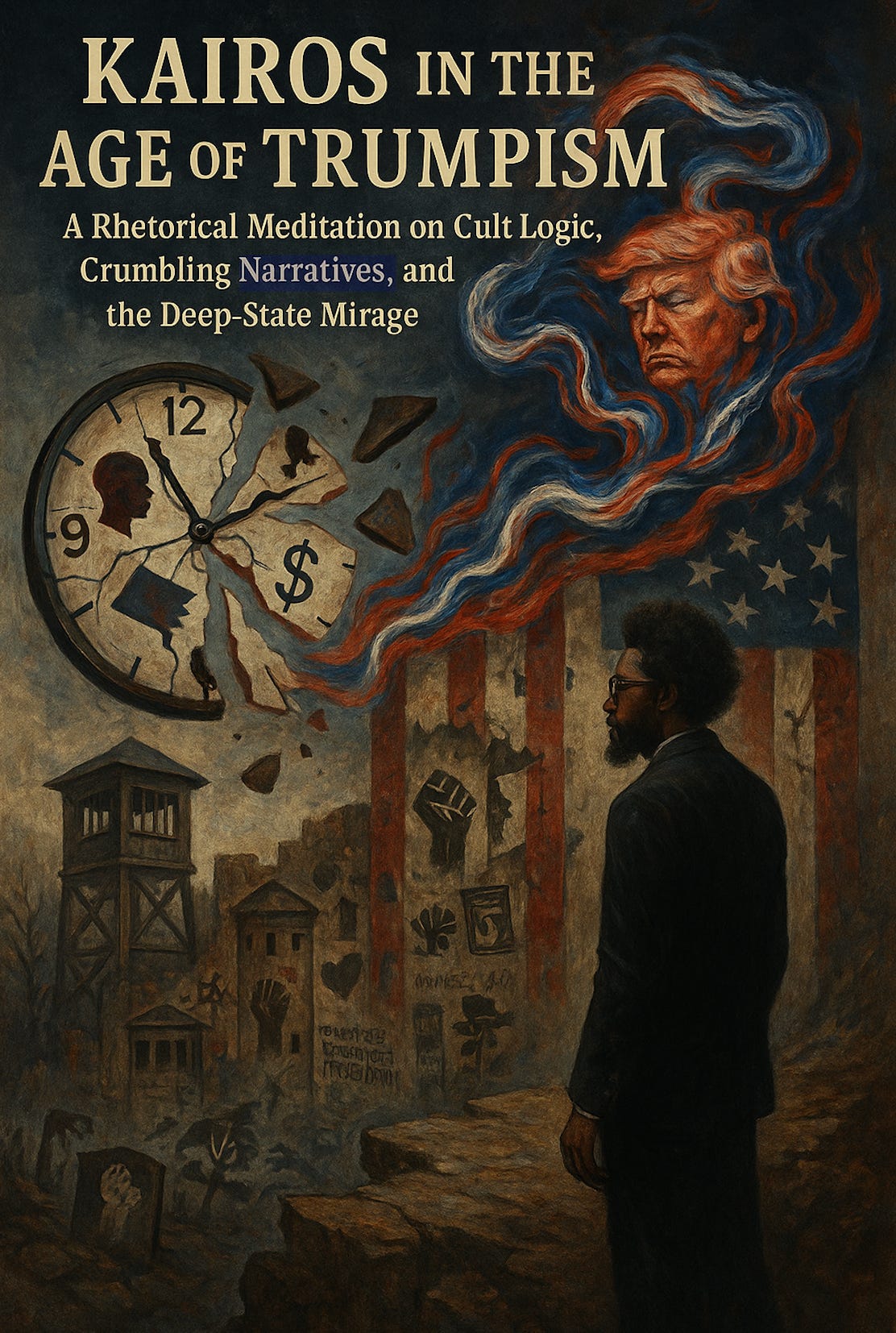

Kairos in the Age of Trumpism: A Rhetorical Meditation on Cult Logic, Crumbling Narratives, and the Deep-State Mirage

This essay explores the power and peril of rhetoric in shaping political identity, belief, and public discourse, using Trumpism and the fallout from the Epstein files as case studies. Drawing on Socratic philosophy, psychoanalytic theory, and media critique, it reveals how rhetorical strategies like whataboutism and spectacle obscure truth and distort perception. Ultimately, it argues that understanding rhetoric—its fallacies, its force, its function—is essential for resisting manipulation and reclaiming collective meaning.

Introduction: Surfing Meaning, Not Chasing “Truth”

Like many of you, I am following the increasing schism between MAGA folks who are insistent that the Epstein files, which purportedly include a client list, are key to unlocking an intricate web of deep-state, democratic monsters, and the MAGA folks who formerly believed these tales but have since backed off of them at Trump’s behest. I am equal parts horrified, ever so slightly amused, apoplectic, and more than a little bit sad.

Two weeks ago, I wrote an article that simultaneously reflected on my time spent in a religious cult and what a cult is and how it functions. Trumpism is a cult. Trump is propped up as a kind of messianic figure replete with near papal infallibility. He demands fealty. Anything less than devotion is viewed by Trump and the Church of Trumpism (which is now inextricably tied to white-centric Evangelical pseudo-Christianity) as blasphemous. One is either all the way in, lock, stock, and barrel, or they are out. That’s precisely how cults work. In a cult, one cannot be part of the in-group, while actively critiquing/challenging/questioning it.

Trumpism as Theology: Messianism, Fealty, and the Discourse of Betrayal

People who built their online persona, their political identity, on uncovering the deep-state often argued that the Epstein files, and the concomitant client list, would light the way. This lis was to function as a flashlight that would illuminate the darkness that enshrouds deep-state actors. Some of these claims, attributed to the QAnon movement, go so far as to claim that there is a group of Democratic and Hollywood elites who are also cannibalistic serial, sexual abusers. This position was their whole jam. Many, though not all, of these folks are MAGA folks. I know this because a pledge to uncover the “deep-state” was one of Trump’s campaign promises. It was a nod to his base. And, just when it seemed that he would finally deliver on his promise, a DOJ memo was leaked that dumped cold water on this long blazing conspiratorial inferno. According to the DOJ, there is no Epstein client list; and he was not murdered (by the Deep State)!

I want to make this point clear: if Epstein’s crimes are real, his victims deserve justice, and the perpetrators of these heinous crimes—crimes purportedly facilitated by Epstein—need to be brought to justice.

Don’t get me wrong, a lot of people both inside and outside of MAGA are upset. But it is almost exclusively MAGA folks whose disappointment is being compounded by a sense of existential betrayal. It’s almost like their deity heard their prayers, promised to part the waters, had them begin to walk into the ocean in faith, then told them that there was, in fact, no way to actually part the waters. They are all drowning on and in a sea of deferred hope. And, instead of saving them, he simply told them to stop complaining about drowning.

I understand where these folks are coming from, kind of. Their hero let them down. That’s never fun. And, in doing so, he stripped away part of their identity kit, which is probably the worst part of all of this (even if they aren’t conscious of it). Folks who feel like they are good people—despite ample evidence to the contrary in some cases—no longer have the ability to rationalize the racism, homophobia, transphobia, and anti-wokeism that they’ve peddled in their crusade against the deep-state agenda.

If Epstein’s list doesn’t exist, it can be argued that neither does the deep state. This has to be a tough pill to swallow. They thought that they would be vindicated. They hoped that once the evidence came out that their family members who have distanced themselves from them would see that they were not crazy. Now, that’s gone. Then, to add insult to, well, insult, their leader told them to just get over it and to stop talking about it. (https://www.npr.org/2025/07/14/nx-s1-5467151/trump-epstein-files-doj-fbi-maga).

And the craziest part is that some of them did. Some of the most prominent Epstein/Deep state proponents simply pulled an Elsa and “let it go” (which then begs the question, were they ever true believers, or were they simply leaches). https://www.the-independent.com/news/world/americas/us-politics/charlie-kirk-epstein-coverage-backtrack-b2789665.html. This is a demonstration of the power of the Church of Trumpism (COT). Trump has reality-warping abilities. His AG stated that the client list was “on her desk”. They next thing we heard, though, is that there is no client list. The math isn’t mathing, as the young folks say. But, for some COT congregants, it doesn’t matter. Trump cannot be wrong; so, despite clear evidence to the contrary, he must be right on this too.

All of this got me thinking about how and why Trumpism is so effective. I already know part of the equation. Trump is a mirror of who this country was and who it is. This country has always favored the few over the many. The favored few share certain commonalities. They were and are generally racialized as white, middle to upper SES, cis-het and straight, and consider themselves Christians of some sort. Trump’s presidency is a constant symbolic, ideological, and legislative nod to these folks. Poor white folks kind of put themselves in the mix even though, for the most part, they do not really reap the same ROI for their investment in whiteness that the former group does.

Nevertheless, poor white peoples are often the most zealous members of the COT. There’s an explanation for this, too, as white-centric, hegemonic ideologies have been distilled down into everyday practices that position whiteness as the ultimate universal equivalent. Whiteness functions as a costume that only conditionally admits poor white folks into the in-group, without actually granting them full admission. I am not saying that poor white folks do not benefit from whiteness at all. They do. Just not in the same way that white higher SES folks do. (I am not going to go into great detail on this here. I have written about this extensively in my books if more resources are needed/wanted.)

That said, for the time being, I want to move away from ideology and instead focus on the actual tool used to spread the gospel of Trumpism—rhetoric. This essay is bifurcated. In Section One, I explore what rhetoric is by analyzing a seminal text in the rhetorical tradition, The Phaedrus, while using rhetorical analysis to better understand the reaction of many ardent anti–Deep Staters to Trump’s decree to “move on” from Epstein—and, essentially, to abandon their obsession with the Deep State. In Section Two, I offer a practical guide—with examples—to help readers better understand rhetoric in action.

Section One: The Power of Rhetoric

My undergraduate degree is in rhetoric. My graduate work was in a program called Language, Literacy, and Culture, which examined how critical theory, rhetorical analysis, and digital media literacy can be harnessed to create opportunities for marginalized students to fully express themselves—or, in the words of Paulo Freire, to “read and write the world” through literacy.

I earned all of my degrees at the University of California, Berkeley. At Berkeley, the Rhetoric Department was—and still is—a kind of intellectual bricolage. A little bit of Marx, a lot of Foucault, some Derrida, a smattering of Judith Butler. A steady diet of Louis Althusser, occasional Hannah Arendt, and when things needed to get spicy, a dash of Frantz Fanon’s psychoanalytic critique of colonial trauma. Semiotics, discourse, power, difference—we looked at how meaning is made: discursively, visually, socially, spatially.

When I was an undergraduate, Berkeley rhetoric defined itself, to a degree, in juxtaposition to or vis-à-vis philosophy. The philosopher is like an astronaut—hovering above, observing the terra incognita of the world in the abstract. But for rhetoricians, the game is different. We’re not astronauts. We’re surfers. We’re in the water. We’re trying to read the wave while riding the wave. We’re still looking for meaning—make no mistake—but not fixed meaning. That distinction matters. Rhetoric is about Kairos, about timing, about context and perspective. It’s about understanding how meaning emerges in motion. And there’s no inherent value judgment in that metaphor—both philosophy and rhetoric are necessary. But they are not the same.

When I taught undergrad rhetoric (rhetorical interpretation), I used to illustrate this with a simple experiment. I’d split the room into two groups and have them sit on opposite sides. Then I’d hold my hand up vertically in the center of the room. On my palm, I’d drawn a red dot. On the back of my hand, a blue dot. Then I’d ask, “What color do you see?”

Predictably, students on one side would say red. The other side said blue.

Then I’d ask: “How confident are you? Would you bet your entire grade on your answer?” Some students would. Others, more cautious, suspected something was up. And they were right.

After the big reveal, I’d tell them something else—total fabrication, of course—but I’d say, “For some reason, students who sit to the right of me during lectures tend to earn higher grades. I can’t explain it, but it’s a real trend.” You can imagine what happened next. Some students got up and moved.

And here’s what mattered: when they moved, the color of the dot they saw changed.

Now, it’s not that the dot itself changed—what they initially saw was still there, still true, but incomplete. What changed was their perspective.

Philosophy, unlike rhetoric, occupies a space of privilege — it speculates from above. Detached. Voyeuristic. Rhetoric, on the other hand, is about immersion. It’s about Kairos — the right word at the right time, in the right place. Rhetoric is not seduced by forms, because forms are forever shifting. It doesn’t wait for the unmoved mover. It rides the flux. It interprets the world by being in the world. The rhetorician is more archaeologist than astronaut. We dig. We get dirty. We read the terrain.

Lots of people, it seems, use the word “rhetoric.” Usually derisively. “Rhetoric from the left.” “Rhetoric from the right.” “That’s just rhetoric.” It was used derisively in Socrates’ time, too—as I’ll get into later. Even the so-called “rhetorical question” carries the implication of manipulation or irrelevance.

But here, I’m not simply interested in defending rhetoric—though I enjoy that fight. I’m interested in doing something deeper. I want to offer a way to understand, identify, and deconstruct some of the rhetorical fallacies that are not only embedded in our media, but are actively shaping our world.

Because rhetoric isn’t just a thing we hear. It’s a thing we live.

The Black Horse, the Charioteer, and the Whataboutism

(A Rhetorical Meditation on Deflection, Fallacy, and the Fight for Meaning)

We are living in a moment where the truth doesn’t just feel contested — it feels liquified. Words, once meant to ground us, now feel like weapons, or worse, distractions—WMD’s if you will (Weapons of Mass Distraction). Nowhere is this more evident than in our political discourse, where truth is less about fidelity to reality and more about rhetorical utility. That’s why now, more than ever, we need media literacy — not just to decode propaganda, but to survive it.

Take whataboutism, for instance. It’s a rhetorical move masquerading as argumentation — a dodge, a redirection. Derived from the Latin tu quoque (“you also”), whataboutism is not concerned with engaging the substance of a claim. It’s a rhetorical sleight-of-hand. Accuse me of something? I’ll just point to your dirt, or someone else’s, and hope the smoke covers the fire. For MAGA folks Joe Biden, the Left, and Libs are the smoke they pay attention to while their leader, the Swamp King, and his swampy court set the world ablaze.

Like I mentioned earlier on, many in MAGA world were obsessed with the unsealing of the Epstein files. It was a rallying cry. The implication? That exposing these names would vindicate the Right and implicate the liberal elite. But now, as the files have fizzled, that same crowd pivots — Whatabout Biden? How come President Biden didn’t release the files (maybe because he did not weaponize the DOJ like Number 47)? What about Hunter? Hillary’s emails! It’s not an answer; it’s simultaneously an evasion and a projection. And it’s rhetorical cowardice. These are not good faith arguments. Probably because many of these folks have placed their faith in something, or someone, else.

The Psychology of Refusal: When Truth Threatens the Self

Tu quque is fundamentally different from a strawman argument. A strawman distorts one’s position and then attacks the distortion, rather than the actual argument. MAGA world is good at this, too. Whataboutism doesn’t even bother engaging with the original position — it just deflects. The difference is subtle but important: one is a misrepresentation; the other is an outright refusal.

And this refusal — this hollowing out of discourse — is dangerous. It’s why understanding rhetorical fallacies isn’t academic nitpicking; it’s survival. It’s why rhetoric, real rhetoric, matters.

Riding the Black Horse: Rhetoric as Soul-Leading in a Post-Truth Age

In The Phaedrus, Socrates claims that the soul is made up of three distinct parts, likening these parts to a charioteer and his two horses: one white and one black. The white horse for Socrates is representative of Philosophy for it is described as:

(T)he one (horse) in better position has an upright appearance, and is clean limbed, high-necked, hook-nosed, white in color, and dark-eyed: his determination to succeed is tempered by self-control and respect for others, which is to say that he is an ally of true glory; and needs no whip but is guided only by spoken commands. (p.238, 254d)

Philosophy is not the only matter Socrates is addressing; he also equates the glorious white horse to non-written speeches and speaking, in general. Socrates privileges speaking over writing; this is no great mystery. He openly contends that nothing written down can be taken seriously. This is of course ironic in that the way we know Socrates’ views on writing is from a written work, from text. Another ironic twist is Socrates’ apparent derision of rhetoric, which is equal to the black horse in Socrates’ description of the tripartite soul.

Ostensibly, Socrates is denouncing rhetoric because it is not after the “truth”; but in actuality and in an unmistakably Socratic twist of irony, Socrates is adamantly calling for the inclusion of rhetoric through his insertion of the dreaded black horse. The black horse is described in a very different way than that of the white horse:

The other (horse) is crooked, over-large, a haphazard jumble of limbs; he has a thick, short neck, and a flat face; he is black in color, with grey, bloodshot eyes, an ally of excess and affection, hairy around the ears, hard of hearing, and scarcely to be controlled with a combination of whip and goad. (254e)

The Charioteer’s Burden: Surfing Meaning Without Drowning in Spectacle

Socrates, while seemingly disparaging rhetoric and writing is, by using the horse and charioteer analogy, arguing for the necessity of writing and rhetoric in the apprehension of beauty or what he considers to be the philosophers’ highest calling: the acquisition of truth. No matter how wayward the second horse is, this horse is a necessary component of both true enlightenment and true fulfillment of the soul. The soul is crucial because, for Socrates, the soul is where truth can be realized. And the quest for truth is the ultimate goal for lovers of beauty, i.e., for philosophers.

The black horse is surely writing; physically, writing throughout the world is black ink on a white page. Of course, there are variations but this combination, by and large, is the most common. The page in this instance, completely devoid of inscriptions, represents the space in which writing seeks to occupy. This space is that of the reader. The third component of this triumvirate is the charioteer; the charioteer is equivalent to the reader for that of written text, or listener in respect to spoken words for it is the charioteer who is pulled to-and-fro by either horse—by either positionality.

The charioteer, however, is not totally without control because it is the charioteer, though naturally resistant to the black horse, that is capable of exerting force to the bit of either horse thereby dictating the path that the horse must take. This tumultuous struggle between the two horses is also the struggle between rhetoric and philosophy.

The black horse is always attempting, with varied success, to overtake the white horse in much the same way that writing on the page of any text is attempting to overtake the page, the available the space, thus insinuating itself as the leading part of the tripartite soul. The charioteer can choose to take the way of the black horse allowing the persuasion of writing/rhetoric to cause him to accept instant gratification, instant pleasure, instead of following the way of philosophy by ignoring what is easier to apprehend and opting to go farther in order to discover universal, definitive truth.

Writing is likened to a parentless child by Socrates, which is unable to defend itself it in the face of “rudeness and unfair abuses.” Socrates makes the claim that writing is incapable of helping itself. Rhetoric, as well as writing, is derided by Socrates, writing for its weakness and rhetoric for its cunning and guile while intentionally (mis)leading souls. At some point they seem to merge into one entity for Socrates. Both rhetoric and writing are equally reprehensible in his view; both are not lovers of the truth, like that of philosophers. Writing can pull away and detach from a fixed meaning. Even though a text is written with intentionality and is unable to change the way it is written, the meaning ascribed to a given text can be different to each reader. Socrates is not cool with that. Not even a little bit.

Rhetoric can perform in much the same way. Great rhetoricians of Socrates time, called sophists, could argue both sides of a given argument with equal success. For Socrates this meant that they had to abandon the truth because according to philosophy truth is fixed; it is not capable of being the truth in one context and untrue in a different context. Perspective doesn’t matter. Writing can deviate from the intentions of the one whom inscribed the writing in the first place; it can move and pull the charioteer in an infinite number of ways, effectively ignoring the thoughts and intentions of the original writer. Rhetoric also has this ability– it can “lead the soul” in a very clear direction and without notice turn that direction upside-down or sideways, thus changing the course of the soul. In this way, it is akin to the dreaded black horse.

The black horse is always seeking to go its own way, to succumb to carnal desires ignoring the aim of the white horse whose pursuit is not animalistic but divine. The black horse is said to be hard to control even when disciplined painfully– it still seeks its own way, it still seeks instant gratification, instant truth. This is also the criticism Socrates levels against rhetoric. Rhetoric, according to Socrates, is not interested in truth only on probability; by this abdication of truth rhetoric renders itself useless.

The distinguishing characteristic of the black horse, its crookedness, is not pertaining to its physical stature but to its abandonment of the truth. Rhetoric is based on perspective; to rhetoricians “truth” is not fixed; rather, it is determined by relative position. This results in it being seen as a “haphazard jumble of limbs.” The parts may not match up perfectly because there is no constant truth with which to reference; as the rhetorician’s perspective changes, the subsequent view of the truth changes.

What is more, rhetoric is not seeking the undeniably timeless, existential truth like that of philosophy; on the contrary, rhetoric is seeking the truth of the present moment--Kairos. Rhetoric is considered “hairy around the ears, hard of hearing, and scarcely to be controlled with a combination of whip and goad” because it is thought to not be seeking functional fixedness. It is seemingly uninterested in Socratic idea of truth. Socrates perhaps inadvertently, perhaps intentionally, acknowledges rhetoric’s pursuit of truth by counting the black horse as a member of the tripartite soul. The soul longs for truth but must settle for a more attainable goal, which is beauty.

The white horse, philosophy, is “tempered by self-control and respect for others, which is to say that he is an ally of true glory” per Socrates. The white horse is content to merely gaze upon beauty, beauty that is unchanging or fixed. This, however, will not suffice for the black horse-rhetoric; the black horse must take possession of the beauty – merely seeing is not enough. The white horse has only a faint desire to possess beauty because for philosophy the truth needs no alteration or manipulation. The black horse, on the contrary, desires to become one with beauty for a time, thereby satisfying its want for instant pleasure, that is, until it is no longer pleasurable, until it is no longer the truth. It must manipulate truth in a way that is beneficial to the position it is positing.

Rhetoric forces the truth, once captured, to conform to its dictates by shaping the truth into the form it desires. For rhetoric the “truth” becomes a reusable tool in the quest to lead souls, rather than a definitive, unchangeable end. For rhetoric, truth is indeed truth, but it is a relative truth, because the truth can be the truth in one situation depending on perspective; this same truth may become untrue if there is a subsequent shift in perspective. Put simply, for rhetoric truth is perspectival.

For Socrates this is unacceptable; the truth from every direction, from any perspective, is the truth; nothing can change it, not perspective nor position nor subject matter. To Socrates, truth is divine and as unchanging as the gods. Nevertheless, Socrates—perhaps unwittingly—describes a kind of conjoined aim for both horses: rhetoric and philosophy both seek to lead the soul to beauty and ultimately to truth, but for differing amounts of time and for differing reasons.

Although Socrates spends an ample amount of time denouncing rhetoric by claiming that rhetoric is nothing more than trickery and craftiness in soul leading, “…Wouldn’t rhetoric, in general, be a kind of skillful leading of the soul by means of words…(261a),” still he includes it in the tripartite soul, which, again, for Socrates is humanity’s truth-seeking mechanism. This inclusion suggests that Socrates is not being completely forthright on his view of the black horse (i.e., rhetoric). More specifically, Socrates, by using this analogy, is arguing that rhetoric is necessary in order to witness beauty and ultimately truth. The soul according to Socrates consists of three parts, the charioteer pulled either by the “bad” black horse or the “good” white horse. Socrates is crafty; however, his craftiness does detract from his intentionality.

Socrates knowingly and intentionally includes the black horse in his tripartite model of the human soul. Clearly, for Socrates, the black horse is needed to balance out the group. Socrates acknowledges that without rhetoric, the black horse (the aforementioned “haphazard jumble of parts” that seduces and captures beauty, at least for a time), the ultimate goal is unattainable.

This is Socrates’ way– irony. He underhandedly denounces and attempts to reduce rhetoric to a gimmick, but all the while he is adamantly arguing, rhetorically, for the usefulness and necessary contribution of rhetoric as a constituent part of the immortal human soul. Without rhetoric, without the black horse, the true lover is unable to see beauty and experience the truth because, for Socrates, the soul is incomplete. Rhetoric—sorry, Socrates—is neither inherently good nor bad. It’s simply a tool.

Socrates, in his distaste for writing and rhetoric, valorizes the white horse, the philosopher’s gaze, and denigrates the black — a position that would echo through centuries of Western thought. But even he couldn’t write the black horse out of the story. The chariot doesn’t move without it.

Freud would later recast this tripartite tension in psychological terms: the id (black horse), ego (charioteer), and superego (white horse). The id isn’t evil; it’s energy. It wants. It moves. Just like rhetoric.

As Michel de Certeau reminds us, rhetoric is not limited to the lecture hall or the pulpit. It lives in the everyday. In the “quotidian.” De Certeau tracks the ways consumers — the ostensibly dominated — create space within the systems that confine them. Tactics. Subversion. Turnings. These are rhetorical acts. Seduction. Resistance. Navigation.

This is where de Certeau’s everyday resistance meets Dr. Adam Banks’ distinctly African American rhetorical tradition. In Race, Rhetoric, and Technology, Banks calls for a reimagined Black rhetoric — one that can confront and bridge the Digital Divide. In a world increasingly governed by the technocratic, Black folks cannot afford to be rhetorically or digitally disenfranchised. Rhetoric — distinctly Black, situationally sharp — becomes the tool, the weapon, the path forward.

Otherwise, the “super information highway” becomes another plantation road. Otherwise, the digital becomes a more elegant form of exclusion. The Goody and Watt “Great Divide” may no longer be about alphabetic literacy — it’s about bandwidth, access, ownership. And rhetoric, again, is how we fight back.

The Psychology of Deflection: When Logic Isn’t the Point

Returning to Whataboutism, it is more than just rhetorical misdirection — it’s psychological deflection. It operates in the realm of emotional self-preservation, not truth-seeking. In fact, psychologists have long studied how people defend themselves against perceived threats to identity, esteem, or worldview. These defenses aren’t always conscious. But they’re real.

According to classic psychoanalytic theory, defense mechanisms — such as denial, projection, and rationalization — help individuals manage internal conflict and external stressors. Anna Freud’s The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense (1936) was foundational in identifying these psychic maneuvers. Whataboutism, in this frame, is a species of projection or displacement. When faced with critique, the ego seeks to externalize blame. “You think I’m wrong? What about you? What about them?” My leader lied—what about your leader’s lies. The target shifts: the goalpost is moved, and the ego is spared.

Contemporary psychology builds on this. In cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), individuals experience psychological discomfort when confronted with conflicting beliefs or behaviors. Rather than change the belief (which is hard), we often change the subject — or the story. Whataboutism is thus a coping strategy to avoid dissonance. It’s not that people don’t understand the original critique. It’s that accepting it might require them to reconsider who they are, what they believe, or how they vote. They may even be forced to reckon with the fallibility of their deity. And that is terrifying.

The Soul’s Struggle for Coherence in an Age of Weaponized Emotion

Jonathan Haidt, in The Righteous Mind (2012), notes that most moral reasoning is post-hoc — we start with intuition and work backwards to justify it. We are not reasoners who occasionally feel; we are feelers who occasionally reason. Whataboutism taps directly into this structure. It’s not an argument designed to win on logic. It’s a performance of indignation meant to protect identity. To maintain psyche coherence.

This is why, when teaching rhetoric or media literacy, we must attend to affect. People aren’t just misinformed; they’re emotionally invested in the stories that sustain their sense of self. Whataboutism isn’t just lazy logic — its trauma response disguised as debate.

We see this in discussions about systemic racism, too. Mention police brutality, and someone inevitably says, What about Black-on-Black crime? It’s not a sincere concern. It’s a deflection — a way to avoid the discomfort of complicity. In that moment, it’s not about truth. It’s about not feeling wrong.

It may feel like I am doing what Socrates did—disparage rhetoric. But, I assure I’m not. I love rhetoric. But, it can be dangerous, which is why we need to be equipped to recognize when it is being used in bad faith. Trumpism deploys rhetoric as a weapon. They use it to make disingenuous arguments based on the centrality of whiteness, racial capitalism, and oligarchy (or more accurately kakistocracy where this admin is concerned). Heather McGhee, in her wonderful book, The Sum of Us argues that at some point we have to stop blaming the people desperate enough to believe would be demagogue’s lies and begin to address the source. I agree to a degree.

This is not dichotomous. It’s both and. We can rebut the source and the true believers. Just know that when we confront these fallacies — when we call out deflection — we aren’t just correcting reasoning. We’re engaging a deeper, often unconscious refusal to be seen, to be challenged, to be changed. We can combat whataboutism—tu quque—by using rhetoric correctly, assertively. But rationality does not Trump (pun intended) fanaticism and zealotry.

Zealots are, by definition, irrational. So, while rhetoric is an incredibly useful tool as is the ability to identify when it is being misused, it’s not magic. Reason only works with reasonable people. Because in the end, rhetoric is not just about the words we say — it’s about the truths we’re willing to face. Or not.

In the meantime, I will be paying attention to whether or not this issues lays the empty rhetoric of Trumpism bare, whether it excoriates it while revealing its mendacity. I hope this the result so that the cult of Trumpism is rationally examined. But, if I am being honest, I believe it will survive this. The COT is strong for the ideological zealots and old timers. I just hope that this issue impels new recruits to take a good long look behind the curtain.

Section Two: The Tools

Syllogistic Reasoning and the Limits of Perspective

Before we talk spectacle, let’s talk syllogisms. Because when rhetoric strays too far into illogic—especially logical fallacies—it loses the tension that makes it powerful. It becomes noise, not signal.

What is a syllogism? Rooted in Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, a syllogism is a three-term deductive argument consisting of two premises and a conclusion—e.g.:

1. All chefs are musicians.

2. Some musicians are painters.

3. Therefore, some chefs are painters.

Simple, right? Yet flawed—this is a valid pattern, but a different structure could produce “nothing follows,” and our intuitions often trip us up (Khemlani & Johnson‑Laird, 2012; Dames et al., 2021).

Here’s the rub: humans are belief-biased. We accept syllogistic conclusions if they feel true, even when they aren’t logically valid (Evans et al., 1983; Nickerson, 1998) . This isn’t merely an academic glitch—it’s foundational. It tells us: our reasoning is frequently post-hoc, an after-the-fact rationalization of intuitively-derived beliefs (Haidt, 2012).

Why mention syllogistic reasoning in a piece on rhetoric and Trumpism? Because it gives us a baseline: a standard of logical clarity. It helps us identify when rhetoric is reasoned versus seductive, when it mobilizes perspective constructively versus when it obscures through fallacy.

Moreover, syllogistic clarity reminds us of what rhetorical reasoning could be: disciplined, coherent, relationship-oriented. Rhetoric isn’t the enemy of logic. It’s the steward of context that activates unsaid premises and affective resonance—when it stays tethered to reason.

Section II: Rhetoric Predicated on Syllogistic Reasoning

Rhetoric at its best is not opposed to deduction—it is grounded in an awareness of syllogistic structure, classical enthymeme, or its modern variants.

What’s an enthymeme? If a syllogism is explicit, an enthymeme is implicit: one premise is left unstated because the audience is assumed to already share it. It’s the arguer’s nudge rather than shove—a shared understanding is presupposed.

This is where Aristotle meets Perelman. Chaïm Perelman’s “new rhetoric” emphasizes that all argumentation seeks audience adherence. We build toward a shared “universal audience” (Perelman & Olbrechts‑Tyteca, 1969) . But to appeal, we must know the syllogistic skeleton—unspoken premises we rely on.

For example:

1. Major premise (unstated): Honest leaks reveal systemic corruption.

2. Minor premise: Epstein files are documented leaks.

3. Conclusion: Epstein files reveal systemic corruption.

If someone then counters: “But what about Biden’s laptop?” they are invoking a new enthymeme—but with the intent to derail, not elaborate. That’s when enthymeme becomes dodge, not dialogue. It is offered as a whataboutism.

In other words, robust rhetoric acknowledges its own logical architecture. Fallacy-prone rhetoric either obscures it or manipulates it.

Section III: Fake News as Spectacle (Debord Revisited)

Enter Guy Debord. In The Society of the Spectacle (1967), he argues that social life in our age has been replaced by representation—by mediated images and stories that obscure reality rather than illuminate it.

He writes: “All that once was directly lived has become mere representation.” We don’t live media. We live through media. We buy, consume, scroll… not necessarily because we need, but because appearing is all we have left.

Fake news is spectacle come full circle. It’s not a glitch of information. It is the vector of spectacle. It is dispersed as Weapons of Mass Distraction. It doesn’t just misinform—it performs, it delivers, it belongs. It thrives in that fusion of show and narrative where verification is optional. And because its point isn’t to enlighten—it’s to persuade, entertain, mobilize—non sequitur becomes acceptable.

In Debord’s terms, discourse is replaced by images of discourse—the emotional resonance, the curated outrage, the viral visuals. Its logic is pathos. Its deployment of spectacle is transparent:

• Magnify an issue—Big!

• Mediatize it—screens, GIFs, TikToks.

• Simplify it—heroes, villains, zero context.

• Push it—share.

It’s junk food for the collective psyche.

Moreover, Debord anticipated non sequitur acceptance when “there is no room for verification”—any equivocation can hold sway (Debord, 1988) . In a world without verification, coherence gives way to spectacle.

Section IV: The Spectacle Permits Non Sequitur

Non sequitur literally means: “it does not follow.” But in spectacle, it matters less if it follows, so long as it feels right emotionally. Rhetorically, this is the pinnacle of detournement—subverting meaning not to critique, but to collapse coherence.

When MAGA supporters pivot from Epstein files to Hunter Biden’s laptop without engaging substance—they’re not reasoning. They’re performing allegiance. That’s why syllogistic grounding matters: it insists rhetoric be reasoned, at least at some structural level.

Spectacle thrives on distraction, deflection, discontinuity. It feasts on non sequiturs. And it normalizes them. So much so that we barely notice.

Section V: Rhetorical Fallacies in the Age of Spectacle

Let’s name some of these rhetorical strategies:

1. Whataboutism:

A classic tu quoque dodge. Magically shifts attention rather than addresses critique. No logic, only closure.

2. Strawman:

Misrepresenting an opponent to knock them down. No real engagement, just spectacle-friendly caricature.

3. Red Herring:

Introduce an irrelevant topic to bury the real one—“Hey, look! Over here!”

4. Begging the question / Circularity:

Offer the conclusion as a premise. Often occurs in AG proclaiming AG is right because AG says so.

5. Appeal to emotion:

Image > argument. Pathos supersedes logos.

All are classical, recognizable—yet spectacle elevates them to micro-tricks embedded in every meme, every viral claim.

Section VI: Rhetoric as Resistance, Reason as Anchor

So, what does real rhetoric look like—one that avoids spectacle but rides its waves? Below, four principles:

1. Make premises explicit: Surface the syllogistic structure—don’t hide it.

2. Anchor in logic—but tune into context: Use enthymeme responsibly, not deceptively.

3. Attend to affect, without letting it dominate: Emotions inform, but don’t annihilate reason.

4. Demand verification, citation, public reasoning: Be a peer in scrutiny, not a preacher in echo.

Classic example: Barack Obama.

He was derided as rhetorically “empty”—too polished, too rehearsed. But polish is rhetoric. As a Black rhetorician, Obama used cadence, narrative, ethos—and syllogistic sense—to transform images (hope, change) into civic vocabulary. That was his power. ()

He wasn’t a spectacle. He was a performance within reason, riding the wave without succumbing to it.

Conclusion: Rhetorical Emancipation in the Spectacle

We live in spectacle-saturated times. Our attention is warped, our thoughts commodified, our perspectives curated. Non sequitur isn’t a bug—it’s a feature. But understanding rhetoric—especially syllogistic reasoning—gives us tools.

Rhetoric isn’t about manipulation. It is, in the best tradition, the responsible stewards of perspective. A rhetorician surfs the wave with the wave—but doesn’t drown in its foam.

If you’ve taught at any level, you’d have lived alongside that black horse and white horse tension. That tension matters. Because without acknowledging how perspective shifts truth, you’re unwittingly complicit in spectacle. You’re just another image in the feed. This is not just true for teachers; it’s true for all of us.

References (APA 7th)

Dames, H., et al. (2021). The stability of syllogistic reasoning performance over time. Journal of Cognitive Psychology. (details from Dames et al., 2021)

Evans, J., et al. (1983). Theoretical accounts of belief bias in syllogistic reasoning. Cognitive Psychology.

Khemlani, H. & Johnson‑Laird, P. N. (2012). Syllogistic reasoning: Core domain in human reasoning research. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology. ()

Perelman, C. & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The new rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation. University of Notre Dame Press.

Debord, G. (1967). The Society of the Spectacle. Buchet-Chastel.

Debord, G. (1988). Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. Verso.

Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books. (Mentioned without direct web citation.)